Printmaking: the technique of making prints

Within the graphic techniques, etching has always been my preference. That was already the case before I entered the art school, the academy Artibus. It is, I find, the technique that gives me most freedom, since what one draws in the wax that covers the etching plate is not yet definite. One can clearly see all that is drawn, since the plates shine through the lines made so easily in the wax. If one does not like the drawing or decides that certain lines are not correct, one takes the small pencil, dips it in the wax and removes the unwanted lines.

A little bit later, when the solvent has evaporated, one can draw again. Only when the (copper or zinc) plate is etched, the lines become definite as small grooves in the plate. When one works at an engraving to make a mistake is disastrous, since one works with a burin directly on the plate. The engraver has to work with more discipline than the etcher. Handling the burin requires a stricter technique that is much more demanding than working with an etching needle.

The etching needle is almost as versatile as a pencil; the drawing pen again is less versatile, since one needs to take into account at every stroke that the ink can flow freely and so one is limited in moving on the paper. Only the printing amounts to the same, since both etching and engraving are the result of an engraving procedure, that is to say, the little grooves are to be filled with printing ink.

When I start on a new etching, I have been outside quite a lot with my sketching book to study nature and something I have made several drawings of topics that interest me. When I at home develop these on the etching plate the perspective lines have to be fixed. That is also the case with those etchings that have come out of my fantasy, like Terminus, located in an imaginary city.

Another technique is dry point. This technique involves scratching lines with a sharp instrument firmly into the plate, mostly with parallel lines, since that produces when printed a better result with regard to the dark parts. One calls the print of such a technique a dry point. The dry point, too, has the characteristics of the engraving procedure, like etching or engraving, since the scratches are filled with ink. But by scratching one produces also a burr just above the surface of the plate that will collect some ink. If one examines the print with a magnifying glass one will discover that in the print such a scratch has one or two extra lines, caused by these burrs. That gives the dry point a velvety feeling.

Some artists have combined these techniques. Rembrandt added frequently the dry point to his bigger etchings in order to get darker shadow parts. That is clearly visible in his etching The Three Crosses.

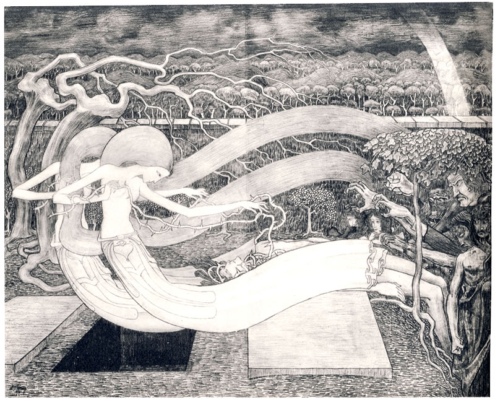

Pieter Dupont combines etching and engraving on the same plate. Some of his plates he has completely engraved, and so the print can rightly be called an engraving. That should not be surprising, since he was educated an engraver of jewellery and silver. And so, like nobody else, with the burin he could put his graceful and curling lines on the plate. The time he lived helped too, since curls and beautiful outlines were much appreciated in the Jugendstil period. The etching technique, though, was not the most appropriate technique to bring out the typical features of the Jugendstil. The woodcut and especially the litho were better. The litho was very popular, since that technique allowed the production of posters in big sizes.

I do not want to deny that in my early years I have been influenced by the Old Masters. When I went on holiday with my parents, I took with me a book with marvellous prints and drawings. Dutch Masters made them from the beginning of the 17th century till the beginning of that last century. One of the drawings in that book that I looked at again and again was by Jan Toorop ‘O Grave where is thy Victory’. It had a tremendous impact on me. When Jan Toorop made this drawing, so around 1891, he made more symbolic work. I have never felt the urge to work in a symbolic manner, nor have I worked, as far as I know, in the manner of another artist.

It is known that one of the greatest Dutch graphic artists, Dirk van Gelder, was strongly influenced by the French graphic artist Bresdin. Some even say that he has become Bresin. If so, he has surpassed his teacher. It is also remarkable that he, in his old age, was able to make good work. That I find encouraging: I, too, hope to be able to continue for years. I have to remark though that his later work became somewhat more archaic. The twenty years that he was teaching at the Koninklijke Haagse Academie he was an excellent teacher.

Sometimes, at ‘open days’, I visit an academy and I have to say that the graphic departments are deplorable. The names of the teachers do not mean anything to me. One hardly finds them at the Internet, since they do not participate in exhibitions: for whatever reason they do not seem to produce anything themselves. On several academies graphic techniques are not longer part of the curriculum. The same is true for ‘illustration’. And although I am describing the situation in the Netherlands, it would not surprise me when in other western countries this would be the same.

My production is not a high one. I work mostly several years at more than one etching plate. If I start in the spring on a new etching, I can only work for a limited period, since an important part of my etchings deal with landscape and are therefore ‘seasonal’. After a few weeks, I have to file the etching till next year. The same is true for other seasonal etchings. That means that normally I am working on three of four etchings.

A special case is an etching that I made in 1975; the end result was not completely satisfying. The public apparently thought so too, since this little etching did not sell at all. So, after some time I destroyed the prints and shelved the plate. Some 34 years later I remembered the incident and searched for the plate. To my dismay, I discovered that the plate was severely damaged by oxidation (see image). I have polished the whole plate very carefully, since I now knew what was wrong with it. It lacked atmosphere.

A few months later I had completely reworked the etching. On my first exhibition organised by a group of artist, de Ploegh, I showed this reworked etching and the public clearly joined me in appreciating this new vision, since the etching was no longer dead stock. If one looks carefully, one can discover that not all the damage is removed.

|

|

In the 17th century the art of etching was at its peak in the Netherlands. Many artists occupied themselves not only with painting or sculpture, but also with etching. In this, too, Rembrandt was foremost. Another artist from this period, who from an point of view of art history, is quite interesting and remarkable is Hercules Seegers, since he was looking for a technique, which allowed him more nuances. Not that many etchings by him are known; he probably has produced more. After his death his experiments were for a long time not continued seriously.

It was only in the 19th century that techniques were developed to etch the plate in such a way that whole areas at once could be put on the plate (aquatint technique). Well known are the series of etching by Francisco Goya, who with great speed but very accurately drew his topics on the etching plate; then he etched and added an aquatint technique, that gives to the print an variety of greys. That was the result of longer or shorter etching those areas. The craftsmanlike and sometimes too dull shading technique could be left aside. Goya did not only use this technique to speed up his work but also to create a dramatic aspect in the etching he had just produced.

An English graphic artist from the second half of the 19th century, whom I encountered for the first time when I glanced through a volume of The Studio (1906) is Sir John Charles Robinson (1824-1913). He left a small oeuvre. I know only a few of his etchings. Two that appeal to me very much are “Newton Manor: Swanage” en “Corfe Castle: Sunshine after rain”.

It is exceptional how he has been able to create the atmospheric circumstance. Although the sun has started to shine, veils of rain are still present. One can clearly see that the etched lines in the air are much lighter than the one on the ground. Normally there is not much difference between the finer and bigger lines when one prints all lines with ink. Possibly the lines that are not intensely black have been etched less deeply. Unfortunately, I cannot ask Sir Robinson how he managed that. Prints of these two etchings can be found in The Tate Gallery.

A friend of Robinson is the graphic artist Sir Francis Seymour Haden (1818 – 1910). One clearly sees that he has studied well Rembrandt’ s etching. Like Rembrandt, he combines etching with dry point technique. But he is not a clone: he only selected a very good teacher. A layperson might be thinking that some of etchings are by Rembrandt, but one can clearly see that the scenes Seymour Haden put on his etching plates are located in England.

Socially and artistically that was an exciting period in England. The Pre-Raphaelites were flowering, Arts and Crafts were established, the Stile Liberty – the English version of the Art Nouveau- announced itself. It was also the period of the expansion of the rail network. Undoubtedly Sir John Charles Robinson and Sir Francis Seymour Haden have made use of the trains around 1870.

The way I started to work was not deliberately chosen. One can clearly see that the drawings I made as a child have been developed over the years into what I have been doing after I left the Academie Artibus (Hogeschool voor Beeldende Kunsten Utrecht).

With the way I practise the etching technique I continue a centuries long tradition. I do have a certain yearning for the past, but I am mostly involved with topics from the present and what I remember from my early years. When I started to etch as an independent artist, the climate in the Netherlands and especially in Utrecht was good. A number of graphic artist were members of the graphic society de Luis. The three most important graphic artists were William Kuik, Charles Donker en Gerard van Rooy (1938 – 2006). The last one has, after his death, technically not been surpassed in this region.

It was only in 1973 that I had produced enough etchings to be able to show them. I was immediately successful. In the Netherlands the art of etching flowered really in the 70’s. Every artist started to etch. But suddenly it all collapsed: that period lasted only for 10 years. Most of the artist returned to their other work. Some diehards like me continued. Fortunately there are some galleries in the Netherlands that specialise in etchings.

On Nov. 30 2002 an exhibition was opened in the Museum ‘t Rembrandthuis (Amsterdam) with graphic work by Charles Donker from Utrecht. He is able to turn his observations of nature in an exemplary manner into etchings. That museum as also presented work by graphic artists that I had not seen before like Gerard de Paleziéux (Zwitserland,1919), Jakob Demus (Oostenrijk, 1959 ) and the Frenchman Erik Desmaziere (1948) who shows in his etchings a masterly example of his insight in space and perspective. I do hope that the Rembrandthuis continues to organise exhibition of artists who work in the Rembrandt-tradition of etching. Until now, the Rembrandthuis is one of the few museums in Northern Europe where one can see contemporary graphic art.

Philip Wiesman

Several galleries are specialised in fine art prints from contemporary printmakers. The following sites are interesting:

www.sfonlinearts.com

www.williampcarlfineprints.com

www.fitch-febvrel.com

www.stoneandpress.com

Explanation and examples of printing techniques: www.emrath.de/mmbei_h.htm